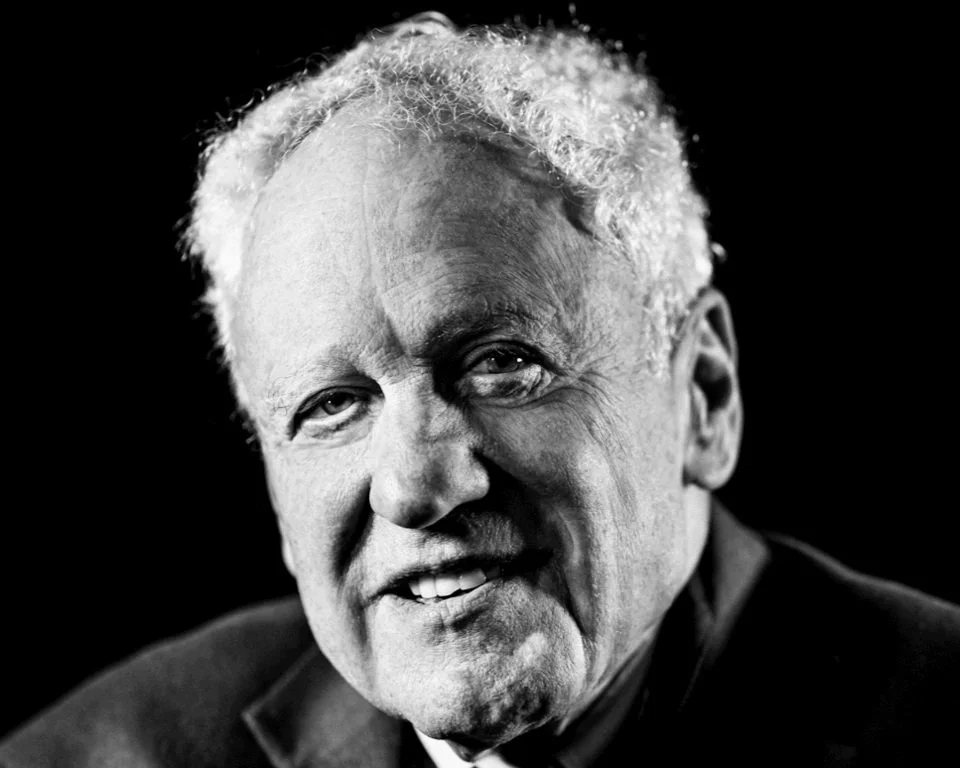

Interview with Alfred Moses

Alfred Moses is an attorney and diplomat who served as the U.S. Ambassador to Romania from 1994 to 1997.

Softball with Jack Kennedy

Contents

Max Raskin: You’ve been in D.C. since the ‘50s — in all your time here, was there someone you met who you thought of as world-historical and just knew you were dealing with someone special?

Alfred Moses: I was enormously impressed with Nelson Mandela when he came to Washington. He was saint-like.

I was enormously impressed with Anwar Sadat when I met with him in Egypt several times. I was very much impressed with Yitzhak Rabin. These people were all very different.

MR: How many presidents have you met?

AM: Probably over half a dozen. Truman, Johnson, Kennedy, Ford, Carter, Reagan, both Bushes, Clinton. Obama, not really. Trump, no. Joe Biden many times. They're the ones that I've met with.

MR: And do any of them stand out among the others?

AM: They were different. Let me just describe them. I was quite young when Truman was president. I was in my twenties. He seemed to be a giant — he wasn't humorous, but he was very direct, very plain-spoken. I was enormously taken.

Kennedy was almost godlike. But again, I was in my early thirties.

MR: You have a funny story about Kennedy.

AM: I knew Jack when he was a senator, we used to play softball together in Georgetown. We were with him when he was running for president, and he was very much taken with my wife, Carol. And he was yacking with her and so he had his arms resting on a corner of a room with nothing between him and the wall but Carol. And as I came over, he said, "Well, it was great talking with you, Carol. I hope to see more of you." And he left. And she turned to me and said, "What would I want to see more of him for?" That was my John Kennedy story.

MR: Did you ever have a conversation with him?

AM: Not in any depth.

I was with him in Hyannisport the night of the election. I had campaigned with him the last three or four days of the campaign and there were two things I remember: We were lost on Long Island in a motorcade that was going the wrong direction. He jumped out of the car at a gas station and asked for directions to get to where we were going. I thought that was a bit unusual.

And then that night we were in Watertown, Connecticut. He was speaking to a crowd on the streets and it was raining. Women were out there in their hair curlers. It was quite a scene. And Kennedy started talking about Munich and Baldwin's capitulation, why England slept, and England's lack of preparedness during the '30s.

And in the middle of his speech, I think he looked up and saw how absurd this was. Here were these women in hair curlers, they had no idea who Stanley Baldwin was. And he broke into laughter…he sort of lost it. I thought that was a very revealing moment, I thought much to his credit. It was all so incongruous.

MR: Who else was on that softball team?

AM: Scoop Jackson played too. He was a congressman, Jack was a congressman, and I was a young Navy officer. It was full of the local softball guys, the guys living in Georgetown. I was living in Georgetown going to night school — law school — at Georgetown and serving in the Navy during the day. We sort of hung around together.

MR: Was Kennedy any good?

AM: Yeah, he was very good. He was a very good athlete.

MR: Was there anyone who was terrible?

AM: Yes. Alfred. I was not one of the better players.

MR: Back to presidents, in a room full of lots of politicians was there someone who dominated the conversation or the scene more than anyone else?

AM: Well, Bill Clinton is a good schmoozer. He was over here a few weeks ago. I had a friend here and he said, "You and President Clinton kept interrupting each other." President Clinton dominated the conversations. Certainly Lyndon Johnson did. Carter and Ford did not. Joe Biden does not.

A Young Buffett

MR: You also got to know Warren Buffett fairly early on, too, right?

AM: Well, I met Warren in the ‘60s. This was before he had Berkshire Hathaway — he had a partnership called Buffett Partnership Limited based out of Kiewit Plaza.

MR: Were you a member of that partnership?

AM: Yes.

MR: Why did you decide to join it?

AM: I had a client and he had been advised to put some money with Buffett who was running a private equity fund. The minimum amount to be invested was $100,000, which in those days was a lot of money. And my client said, "Before I invest, I want you to meet him and you tell me what you think." So I arranged to meet with Warren in Grand Central Station for lunch.

I thought he was enormously impressive. I told my client I thought that he'd be well-advised to put $100,000 in with Buffett. He said to me, "No, I'll put in 80, my wife will put in 15, but I want you to be in too for five. So if you go in, I'll go in."

So he called Buffett and Buffett said if the aggregate was $100,000 he would accept it. So I put in $5,000. It was that thoughtless on my part. I was simply following the advice I'd given to my client and that turned out to be a great investment.

MR: What was it about him that impressed you so quickly?

AM: He was an original thinker — he had done well.

He had made a big bet on American Express right after it had been subjected to a scandal by a guy named De Angelis who had borrowed money from American Express with the collateral being ammonia tanks, which were used as fertilizer for farmers. There was only one problem — there was no ammonium in the tanks. So the loan went sour.

Warren figured out that American Express, with its credit cards, had a business that was worth more than the stock price. So despite the loss on the ammonia tanks, it was a good investment. Warren put a good deal of money in American Express.

And by the time I met him, American Express had recovered and Warren had been proven right. He had also invested money in a credit life insurance company in Baltimore. I knew the principals. Warren put some money in, made a quick profit, took his money out. So I thought this was a very smart guy. He was living in Omaha, following investments everywhere, relying on his own acuity and had done well. And I thought he would continue to do well.

MR: Did you find him personally charming?

AM: No, he's not. He wasn't then a charmer at all. He was a bit nervous, talked very quickly. But I found him substantively sound. He then turned out to be avuncular, but in those days he was nothing like that.

MR: Were there any other people that you spotted before anyone else and knew that they were going to be special?

AM: Yes. Mark Jacobsen — he started a financial intermediary that he sold for two and a half billion. It's now worth 10 billion. It was solely his creation. He's turned out to be a big winner.

Codex Moses

MR: You read a lot and have a big library — who are your favorite novelists and who your favorite historians are?

AM: Ishiguro, one of the current novelists. Robert Caro is enormously able. McCullough was enormously able. General Grant's memoirs are absolutely superb. I would put Herodotus up there.

MR: Your purchase of the Codex Sassoon was obviously a big deal. Is there anything else that you collect?

AM: Art.

MR: Who's your favorite artist? Or who do you think you own the most pieces from?

AM: Probably Hans Hoffmann, but he's not my favorite artist. I've got a wonderful Chagall. I've got two great Kandinsky’s.

MR: Oh, wow.

AM: I've got a de Kooning, and I’ve got two Rudolf Bauer’s I'm very fond of.

MR: What was the first piece of art you collected?

AM: Oh, the first piece I collected I discarded because I kept moving up in the price range. I bought two Bolotowskys and a Wolf Kahn in '73. Carol bought a Chagall lithograph in the early seventies, which is very nice.

MR: All these artists — Chagall, Bolotowsky, Hoffmann — they're all abstract.

AM: Correct.

MR: What appeals to you about that?

AM: I like the color. I like the pseudo-Cubists.

I call pseudo-cubists…adaptations of Cubism. I don't like representational art. I never have. It's what I grew up with in people's homes when I was a kid. And I don't look back, I look ahead, so I have never collected representational art.

Dreams and Ambitions

MR: It seems like a lot of what you've done in life has not been planned. The art you collected you just happen to like, and it turned out to be extremely valuable later on.

AM: I think that's right, Max. I think I was always very ambitious. Some of the things I've done in my life — most of the things — I never anticipated I would do. I never thought I'd go to the law firm…it was well beyond my sights. I never thought I'd end up in the White House or as an ambassador. I never thought I'd be president of the American Jewish Committee. All those things were well beyond anything I aspired to be.

MR: But you did say you're ambitious. What advice do you have to someone who wants to do good and also have an interesting, successful life?

AM: Follow your dreams.

MR: When you were in your 20s and 30s what did you want out of life?

AM: I don't think I thought about it, but subliminally, I think I wanted to be economically successful. I certainly wanted to be able to not have to worry about money. My father had worried so much. I wanted to be a respected person in the community, and I think I wanted to contribute to humankind. And I wanted to be a faithful Jew. I think all four of those so-called ambitions were part of my makeup.

I fulfilled my ambitions. I don't feel I was a failure. There've been areas in which I have not lived up to what I would like to have done.

MR: What's an area where you don't think you've lived up to it?

AM: Well, on the personal side, not every relationship has been perfect.

MR: What advice would you give to your younger self?

AM: Don't be quite as ambitious as I was.

That's a good question. I don't know. I feel good about my four children. I feel I have been a constructive influence in their lives. I'm thankful that I and my four children get along. Not only get along but love each other and are mutually supportive.

I'm very thankful for my two wonderful wives, children, and 12 grandchildren. I love them all, and I think we're close. I'm very thankful for my friends. People have been wonderful to me all my life. I could not have achieved any of the things that I was able to do were it not for friends and their support. I've been the beneficiary of the kindness of many people.

Dartmouth

MR: You're the longest member of Kesher Israel, the synagogue in Georgetown, correct?

AM: Yes.

MR: What was the worst antisemitism that you ever experienced?

AM: Maybe minor incidents but nothing of significance. I was never deterred by antisemitism. Antisemitism is not my problem. It's the problem of the antisemites.

MR: Did anyone ever say anything to you?

AM: Oh, of course.

MR: Do you remember anything specifically?

AM: Oh, I don't know. I tend to totally disregard it.

MR: Did it ever get physical?

AM: No.

MR: You were a Jew in Dartmouth in the 1950s — what was that like?

AM: I think I was the only observant Jew at Dartmouth. I was the only one who kept kosher.

MR: Wow. Did your peers find it an oddity or did people not know?

AM: I think people did not know. I was also a shomer Shabbat.

MR: What did your parents do?

AM: My father was a hatmaker.

MR: Do you resent Kennedy for hurting the family business?

AM: My father did, but I was already a practicing lawyer.

MR: Your father resented Kennedy for not wearing a hat during his inauguration?

AM: Yes.

From Shul to the Vatican and Back

MR: You met the Pope once?

AM: I was in Israel and I had an appointment to see the Pope. I flew Alitalia from Tel Aviv to Rome.

MR: Which Pope was this?

AM: John Paul.

MR: And what was he like?

AM: He was very friendly, very engaging, very Polish. He'd come from Krakow. He had many Jewish friends.

MR: When you think about your childhood, your Judaism growing up, what memories come to mind?

AM: Primarily our Orthodox synagogue.

MR: What was it called?

AM: Shearith Israel in Baltimore.

MR: And what were your memories?

AM: The rabbi, walking to shul, sitting with my father, his brother, and cousin. The davening. It was very strict. You had to wear a hat. You couldn't wear a kippah. No tennis shoes. They wouldn't let Hassidim in. It was a very frum, Agudah, German congregation.

Family Tree

MR: Where's your family from?

AM: On my mother's side, they were from Holland and Germany, Bavaria; my father's side from Hesse-Kassel in Germany and Poznan in Poland. There were more Deutsche Juden than Ostjuden. They came here 150 years ago or more. My father and mother were both born in the United States.

MR: When you think about your mother and father, what stands out about both of them?

AM: Well, my mother was enormously intelligent. A marvelous manager, quite ambitious.

MR: How old did she live to be?

AM: Almost 94.

AM: My father was also extremely intelligent, somewhat frustrated in his business, I think.

MR: How old did he live?

AM: 92.

MR: So he lived to see a lot of your success?

AM: I guess by the time he died I was successful, but in my early years I was a bit of a miscreant, and when I ended up being what you call successful, he said to me, "Alfred, I never thought you'd succeed," so he had doubts about me.

MR: When you say you were a miscreant, what do you mean by that?

AM: I was a poor student in grammar school. I was a poor student in junior high school. I was an okay student in high school. I got into scrapes. I was quite belligerent, and my older sister told me I was very stubborn. I think that's true, I still am. That's all I can tell you.

MR: What turned things around for you?

AM: Maturity.

MR: Was there a person or event that changed you?

AM: No, I think it was evolutionary.