Interview with Michael Savage

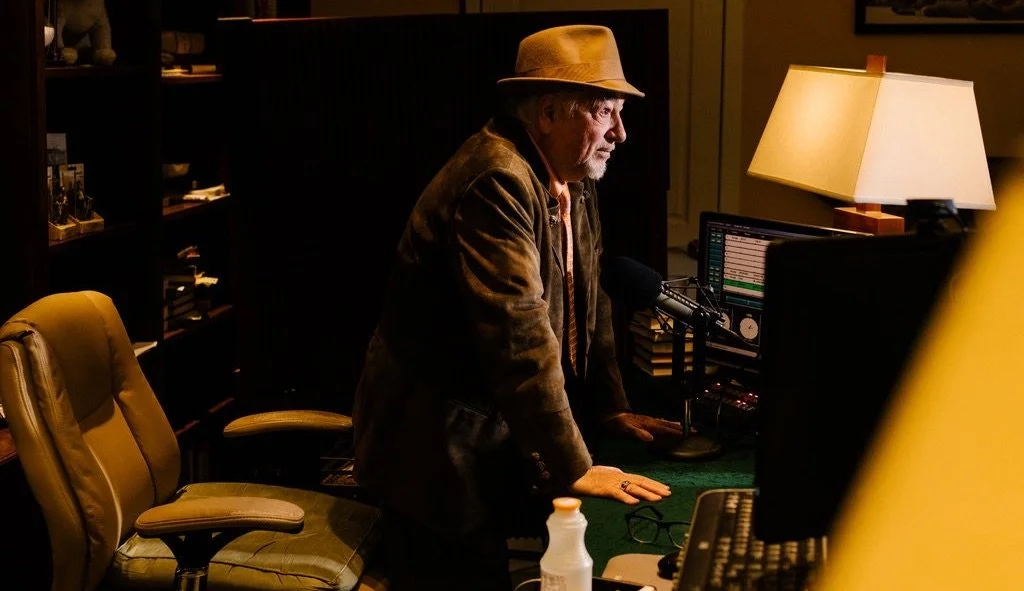

Michael Savage is an author, radio host, and ethnobotanist. He has written 29 books and is the host of The Savage Nation. Savage was inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame in 2016. He received his doctorate in ethnomedicine from U.C. Berkeley and is the founder of the Healing Wheel Society.

John Coltrane and the Poetry of Michael Savage

Contents

Max Raskin: I want to start by asking about the 2008 profile of you in the New Yorker. It made such an impression on me when it came out. Do you remember it? It was Kelefa Sanneh.

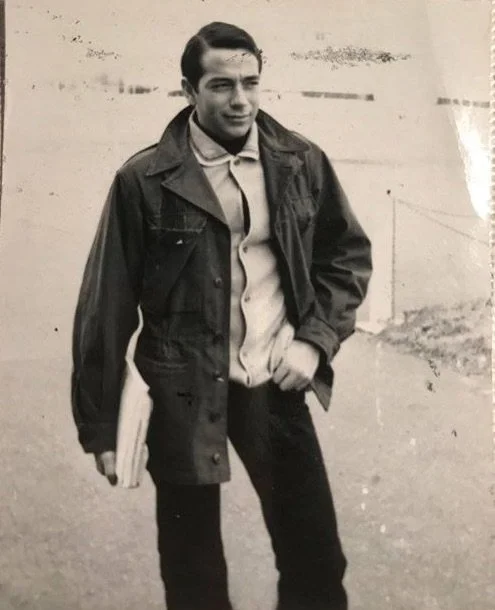

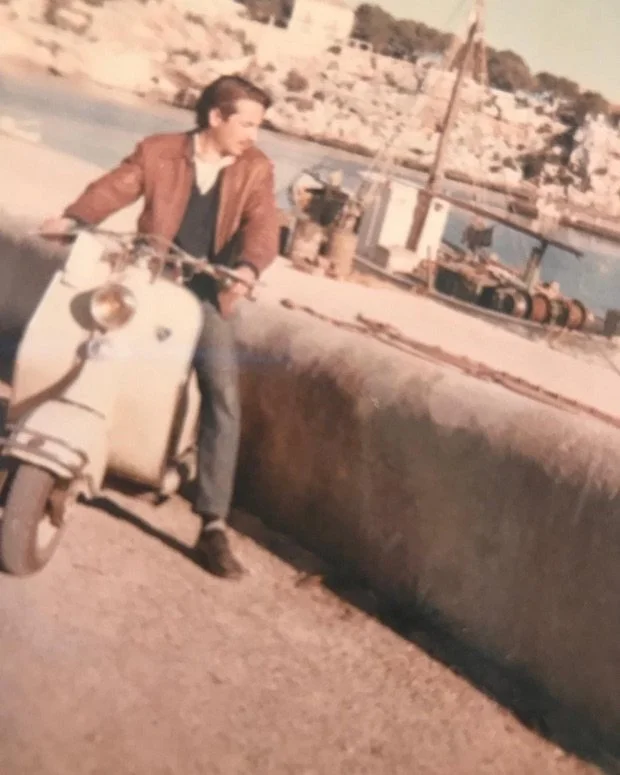

Michael Savage: Listen, I stay in touch with Kelefa. He wrote the profile of me, which was, at the time, the high point of my media life because I grew up reading the New Yorker. I was a poor kid from Queens, but very into books, very into music — jazz music, in particular. So, when anyone was profiled in the New Yorker people thought, "Oh, my God. Who are they?"

MR: What kind of jazz did you listen to growing up?

MS: I still do. They’re all condensed into this one little Blue Note volume. I'll tell you the ones that I'm stuck on: I grew up loving Cannonball Adderley when I was 17. Art Blakey. John Coltrane.

MR: You like Coltrane?

MS: I do. I truly do.

MR: Do you find it too obscure?

MS: No, because when he goes on to a so-called musical trail, I understand what's going on inside his soul. I mean, I could feel him with the horn.

So, there's a young saxophone player, Sam Gendel, who used to listen to me, and about 15 years ago, he sent me a thing called the Found Poetry of Michael Savage. He had listened to the show and took out poetry from my monologues, which were not poetry. He would take out sections and turn them into poetry. He wrote a whole book on it. We met. He turns out to be a jazz saxophonist.

Taking it back to Kelefa Sanneh, I introduced him to Kelefa, who was formerly a music critic for the New York Times. They met, and he did a profile of this young saxophonist. They became friends over me.

MR: Do you think your piece holds up?

MS: It's funny that you ask. I looked at it the other day. It's set in a time. Would I think the same of it today as I did in ‘09? No.

He was talking about the “party of one.” How I was always talking about dying and death. That's what he was saying.

MR: I remember that.

MS: Well, I still am. I'm obsessed with this whole issue of mortality. I have been since I'm a kid, since I'm five years old. I'm in my ninth decade, Max. No one lives forever.

MR: On one of your recent shows, you read a part of Psalm 90: The span of our life is seventy years, or, given the strength, eighty years; but the best of them are trouble and sorrow. They pass by speedily, and we are in darkness.

MS: That's right. And I said, "Michael, wake up. You're still living like you're going to live forever. You're still acting like you're immortal. You won't stop and slow down and mentally stop it." So, I don't know how to change and become my age.

MR: What age do you feel?

MS: I don't feel like a certain age. I don't know. Your body certainly tells you you're not the same age that you were.

MR: What's the worst part about getting old physically?

MS: I don't know. I've been very lucky so far. I've had only one incident with a coronary issue in ‘09.

Churchillian Naps and Savage Dreams

MR: I want to ask you about napping. My interviews came about because I was always interested in Churchill’s habits, including his naps. Do you nap?

MS: I nap every day, 100%. I have since I'm 40. As often as I could.

MR: And how long do you nap for?

MS: I'm a very Mediterranean man — more the siesta-type nap. I don't sleep for two hours. I lay down for 20, 30 minutes. That's all I can handle.

MR: And when do you do it, generally?

MS: Three o'clock. Later than that, not too good.

MR: Churchill would put his nightgown on and get into bed and nap for an hour.

MS: That I understand. I do too. I get into bed like I'm going to sleep for the night. I pull the shades.

MR: Really?

MS: Here's the thing about napping that people should understand. I read that in Japanese factories, they would stop everything in the factories and turn off all the lights twice a day for 10 minutes, and everybody would cover their eyes with their hands or a mask. The brain uses 20% of all of the blood glucose in the body. The brain and the eyes are connected. The eyes are a huge consumer of our energy. Think about it. So, if you shut down the light, you're not consuming the blood glucose…your brain is also resting. That's it. It's that simple.

MR: Do you dream?

MS: Oh, every night is another CinemaScope adventure.

MR: Did you ever take psychoanalysis seriously, or did you think it was nonsense?

MS: Oh, no, I absolutely am a firm believer in psychoanalysis. I read Freud when I was 18, so I totally believe in the subconscious mind, and I tap into it. I remember all my dreams.

MR: Do you have a notebook by the side of your bed?

MS: Great you should ask. One of the tricks that I was going to teach the next generation is keep a notebook by your bed — not a recorder…a notebook. The most fertile dreams are at dawn. Everybody knows that. The waking state between sleep and consciousness is the most productive, creative part of the day for most creative people in terms of new ideas.

I grew up in Queens. None of my family was college educated. They were inherently smart. And I had a relative that I never met in Brooklyn. The more educated side of the family was from Brooklyn. And this guy, let's call him Manny, the engineer. I would hear stories whispered by the women, "Manny is so smart that he keeps a notebook by his bed and he writes down his ideas in the middle of the night." No one ever said it to me. I overheard it. I said, "That sounds like a great idea."

You see how kids learn? Why do I hear that and not something else? Why do I sit in the geometry class falling asleep, except I hear certain things? Why, in a social studies class, falling asleep, but certain things stick? I don't know.

MR: This is like how August Kekulé discovered the benzene ring when he dreamed of a snake eating itself.

MS: Oh, my God. I didn't know that.

MR: You just talked about creativity — do you primarily think of yourself as a writer or a speaker? What’s your primary outlet?

MS: I'm speechless.

[Pauses]

It’s hard to separate the writer from the speaker. It's hard to separate the orator from the writer because if you're an orator, the thoughts are generated within your head, based on your own thoughts, based on your observations, based upon the writings or thoughts of others that trigger some things in yourself. I've been writing since I'm rather young. I mean, I've been talking since I was younger. I've been talking since I'm five or six. Who knows?

MR: What's the earliest recording of you?

MS: We don't have it. My friend's family lived in Wantagh, Long Island — they were richer than us and bought a single-family house — and he got a recorder. And I remember we were playing with the recorder in his basement out on Long Island, and I heard my own voice. I thought, "That's amazing."

Bottle of Red, Bottle of White

MS: You triggered me with the benzene ring. I studied organic chemistry. I studied medicinal chemistry. I studied under one of the most famous medicinal chemists in the world. People don't know that.

MR: I read in the early days you met Timothy Leary at one point?

MS: I do. I remember going up to him. I was extremely shy at the time. We went up to Millbrook, New York. They were using an estate that some rich kid gave them, and they turned it into like an ashram. And I didn't use LSD. I still don't. I hate it. I hate any psychedelic drug.

MR: Have you ever taken it?

MS: No. And I just know what marijuana did to me. I hated it. I smoked it for years when I was 17 because all my friends did, but it was never good for me because my mind is far too active.

MR: Freud famously used cocaine — did you ever try that?

MS: I tried it. I hated it.

MR: Do you drink coffee?

MS: Yes, I have about a half a cup in the morning every day.

MR: But that's it? Only a half a cup?

MS: Yeah, I can't drink anymore. I mean, I feel it immediately. I'm extremely reactive to it.

MS: You're more scattered than I am right now. We've gone from what I think of the benzene ring to how much coffee I drink. I love it.

MR: I know! That’s how I do it. You appreciate jazz.

Turning back to drinking — do you enjoy drinking alcohol?

MS: Mm-hmm-hmm.

MR: I know you like red wine.

MS: No, no, I don't drink red wine. I drink white wine almost exclusively.

MR: You used to drink red wine? I remember you talking about it on the show.

MS: In the winter, when it's cold, I will drink red wine. I've talked about it on my cooking shows — if I drink red wine in the warm weather, I get a smashing headache. My body changes. I'm a natural organism, a natural man. When the weather turns cold, I drink red wine. It warms me up. In the summertime, this time of year, all the way through, a certain Sauvignon Blanc — a cheap white wine from California is what I'm drinking now.

MR: Do you snack during the day?

MS: Yes, I definitely try to keep my blood sugar up.

MR: And you don’t eat meat very much?

MS: Once a month, at most.

MR: How often do you think about Teddy?

MS: You really are jumping around here now. You go from meat to my dead dog. I love it. That's also connected in a way, by the way. Because you say meat, you think of a corpse.

Okay I got it. I understand your mind…I need to be your psychiatrist. If you go to Katz's Delicatessen, you think of all your dead animals?

MR: I don't eat at Katz's. It's not kosher.

MS: Teddy was my spirit guide. He lived with me for 17 years. I've never gotten over his loss. I still am broken. A piece of me is gone. That's all.

MR: What losses in your life do you think has been the hardest for you?

MS: My brother, my father, my mother, my dog.

Dogmas of the Not-So Quiet Past

MR: Have you ever been in therapy?

MS: Yes. There's nothing hidden about it. I don't think it's a secret.

Here’s the thing about therapy — therapy is talking to a friend who listens to you and asks good questions. That's really what therapy is. In another time, when we lived in a village and people were close to each other, people didn't need therapists. They had a rabbi, number one, and they had friends, number two. So, if they didn't feel good, they went for a walk with their friend, and they said, "You know, Max, I don't feel good today. I was thinking about my deceased uncle." And the friend says, "Why are you thinking about him?" And they talked, and they didn't get a bill in the morning for $600.

Are you a pious, practicing Orthodox Jewish person?

MR: Yes

MS: Well, because I'm very affiliated with the Chabad people. I have been for 40 years.

MR: I have a couple of questions that I want to ask you about religion. You say you’re neither proud nor not proud of not being religious — it’s just the facts. Were there times in your life when you were more doctrinally observant about certain things?

MS: My father was an atheist from Russia. Didn't believe in God. A little boy on the streets of New York, holding dad's hand. Dad is God. "Dad, do you believe in God?

“What happens when we die?"

He said, "There is no God. When I die, you could throw me in a garbage can."

Now, think about what that does to a child, the trauma of thinking of his father curled up in a garbage can. I never got over that one. So I’m in and out with God, in and out with God, in and out with God, in and out with God.

The last terrible thing I ever did with regard to God — Queens, New York, it was Yom Kippur — I was 21 years old. I was in my sports car and everyone was outside the Hillcrest Jewish Center, standing outside during a break.

I go by with my sports car and make it backfire so everyone would look at me.

What I did was I turned my back on my tribe. I turned my back on my people, and God cast me out because he let me cast myself out. It took me 30 years to come back to my people from that day. I got punished by doing it, but there's always something positive in the negative. The yetzer hara — the evil impulse — can also be used for good. And I learned later in life from a mystical Chassidic rabbi that those with the strongest evil impulse can do the greatest good.

MR: That’s black and white in the Gemara!

MS: That’s such an important point. If prisoners who have a revelation in jail, whether it be Christianity, or Judaism, or Islam, they come to understand that although they've done evil, they could come to understand that their energy is so strong that if they learn to channel that evil energy, the evil impulse, the yetzer hara, they can do the greatest good on earth. They can move mountains.

MR: Have you ever flirted with dogma though? Not eating pork, wearing tefillin, et cetera.

MS: No, not really because I don't think religion requires dogmatic behavior. I think that the object of religion is to bring you to the best part of yourself through God and to worship God period, end the story.

We must remember that we have a jealous God up there, or out there, or around us. He's not a nice guy. I've said this before. God is not a nice guy. He's not Mr. Rogers. He's not our friend. He gets mad really easy and he can really fuck us up, so that's about it. I mean, you got to be very careful because I've met Orthodox people who do everything according to the book, and they're assholes.

MR: You make it very clear in your shows that you really hate hypocrisy when it comes to religion. Ramban calls it being a scoundrel with the “permission” of the Torah. But do you think it’s possible for those irrational dogmas to actually be worth doing?

MS: I don't want to knock anyone who does anything that is important to them…

MR: …but it's not you? You never flirted with it?

MS: No. I never saw any value in such behavioral aspects.

[Begins reciting Psalm 90:]

A prayer by Moses…the years of our life number 70, if in great vigor, 80; Most of them are, but travail and futility. Passing quickly and flying away.

Bingo.

I saw this Rosh Hashanah in the morning prayers for Rosh Hashanah. It was very hard for me this year. I couldn't get into it. And I'll tell you something funny. I came home from Rosh Hashanah at Chabad, and I did a YouTube that was a little mocking. I felt terrible. And I took it down the next day, and I said, "You want to be the kid who drives by the synagogue again with the backfiring car at age 82? Play with God now. Go see who wins."

MR: That’s incredible.

MS: I just took it down. I said, "Don't be a jerk at your age."

MR: You have this incredible ability to really nail someone yet you also have this sensitive soul. Do you often find yourself regretting things you say, or you mostly feel like you get it right?

MS: These days, I get it right almost all the time. I try to avoid interacting with people I don't like so I don't get in trouble. I'm also mostly a hermit. I rarely say something I regret because I don't talk to too many people.

MR: Except for millions of people.

MS: But listen, I still think about saying things to people. I have Trump signs on my gate and for example, what if someone says something to me? What are you going to say to them? You're going to cut them to ribbons? You're going to be reasonable? Or you're going to shrug and walk on like an Italian. At this age, I would shrug and walk on like an Italian. Why engage with everyone over every fakaktah thing that they say?

Mike’s Mics

MR: How long do you have for this interview, by the way?

MS: Just keep going. We'll go like we're playing a musical piece together. Let's do a riff.

MR: Music is obviously extremely important to you.

MS: Totally.

MR: Is live music important to you, or is it just recordings?

MS: It's all recorded. I don't go to clubs because I don't like crowds.

MR: And is that true your whole life?

MS: No. I went to jazz shows in New York City when I lived there when I was younger. I used to go to the Village Gate and the Village Vanguard. I saw Lenny Bruce live. But I lived for the weekends to go to Latin nightclubs like the Palladium to hear the great salsa music of the day. I saw Johnny Pacheco live. José Fajardo. Eddie Palmieri and Charlie Palmieri. Tito Puente. Let me throw another name out there: Machito. I saw and danced to some of the great Latin music. It keep me going in my darkest times.

But I'm not a crowd person now. I get rattled in crowds. I'll tell you why. My brain is developed in a way that I pick things up on a more sensitive level. Any sensitive person, any creative person picks things up, or they wouldn't be a creator. So, if you go in a crowd, you're picking up all the vibrations of the mob, the herd, the grunting, the groaning, the smells, the shoving. I feel like a cow in a pen. I don't like crowds.

MR: And you can't dissociate from that.

MS: No. That's why I'm trouble in restaurants. You don't want to eat with me in a restaurant. My family gave up years ago. They know. They know I'm too sensitive. I can hear people talking three tables away.

I prefer quiet. I prefer feeding the seagulls off my house. I prefer a small bike ride around my neighborhood.

MR: What kind of bike do you have?

MS: I have two bicycles. I have a Bianchi something or other, not a very expensive one, a cafe cruiser. They're simple 10-speed bikes. They're not the $12,000 bicycles.

MR: Are you a feinschmecker about anything?

MS: It’s an interesting question you're asking me, and I've only come to a new revelation in the last few days. You'll be the first to hear it. I'm a fairly wealthy man. I've earned it all. Okay. And yet I don't live up to the standards of my income. Most people in America live beyond of what they earn. So, if they made $300,000 a year, they live like they're worth $30 million a year. They borrow whatever they have to do to show off, and that's why they're jumping out of windows in New York.

MR: So you don’t have anything?

MS: Cars were an indulgence of mine. If they were truly important to me, I would buy a new, expensive something or other.

MR: But your glasses, for instance. Where are they from?

MS: LensCrafters.

MR: What about your clothes?

MS: This is from Amazon — it’s a cheap knockoff because it's the softest of all the fabrics.

I'm also a collector of paintings and of bronzes and clocks because my dad was an antique dealer. I challenged my audience, "Who painted these? Is there an art critic in the audience?" Nobody knew. They said, "Oh, you painted them." I didn't paint them. It's by Bernhard Gutmann, lived 1869 to 1936. I bought them at a Bonhams auction in 2017 for about $5,700 each. That's not a lot of money. It's not great art. It's not Picasso.

MR: I want to talk to you about microphones. What's your favorite microphone?

MS: Well, I use this RE27. This is the workhorse of the broadcasting industry.

MR: Most people buy these Shure mics today.

MS: Well, they don't understand broadcasting as well as I do.

MR: I want to ask you about your radio influences. Who taught you about broadcasting? Who were you listening to?

MS: No, it was born in me. It's like, “How did John Coltrane learn to play the saxophone?”

MR: What about the technical aspects?

MS: Nobody, nobody. I never listened to talk radio before I went on the air.

MR: Really?

MS: I heard Limbaugh once in a while. I wasn't impressed with him. I heard Howard Stern. I thought he was a jackass.

MR: There's this whole generation of Joe Rogans — is there anyone that catches your eye as you get older? Is there someone that you think of as carrying on your legacy?

MS: Well, it'd be egotistical for me to say no, and it would be egotistical for me to say yes.

Let's talk about Joe Rogan for a minute. I've listened to him maybe for a few seconds. He seems to be a meathead to me, a two-dimensional meathead who has struck a chord with the average person out there who likes brutish, thuggish, not deep-thinking kind of guys.

MR: But it’s authentic?

MS: I don't know. But the thing is, they like him, and I respect that.

You know, you're interesting. You're asking a question I never answered, which is what got me into voices. When I was a little kid, I used to like movies, like every kid. And sometimes before the movie there were documentaries — like travel documentaries.

And there was some guy who had a great voice, so I listened to him.

Also, “This is Mel Allen in Yankee Stadium. It's a high fly ball to center field.” Oh, man. Who didn't feel that ball flying through the air?

MR: Were you a baseball fan when you were growing up?

MS: Yes, I was a Yankees nut. I have a baseball from Yankee Stadium, 1954, hardball.

MR: Who was the player you looked up to?

MS: Mickey Mantle. Oh, he was my hero. Mickey Mantle.

Vitamins and Barbells

MR: You’ve written a large number of books — 27?

MS: I can't keep track. 29 published, I guess.

MR: If you could just recommend one book, which would be the book that you're most proud of or that comes to mind?

MS: I'd have to ask you a question to tell you the answer to that. What's the age demographic of your readers?

MR: I don’t think I can say because you’ll get people interested in Noam Chomsky and some in Lindsey Metselaar.

MS: The most important book: my first published book was called Earth Medicine, Earth Foods about American Indian remedies. It's an important book. God, Faith, and Reason may last the longest of all my books. But the most interesting may be A Savage Life which is my autobiography.

MR: If you had to give young men one piece of nutritional or medical advice, what would it be?

MS: Don't smoke pot, number one. Cannabis is the most dangerous drug on the planet because people think it's benign. It addles up the brain in ways they don't know. In fact, the more addicted they are, the more they deny they're addicted. That's number one.

MR: What about vitamins?

MS: I start every day with a multivitamin. I absolutely am addicted to vitamin C. Vitamin C powder is number one. Here’s the thing about vitamin C people don't understand — and I've studied it with the best minds in the history of vitamin C…Cathcart and Kunin lived on this stuff and helped tens of thousands of patients — the sicker you are, the more vitamin C you can take without developing bowel intolerance. That's the Cathcart hypothesis. That means if you're healthy, you can take about 1,000 milligrams a day. If you take more than that, you're going to get an upset bowel because your body doesn't need the ascorbate. If you're sick, you could take three, four grams.

Most people say they took vitamin C and it did nothing. That’s because they took inactive vitamins that are being sold in a drug store or in a health food store by shyster companies, and it's garbage. It's not active stuff. So, I buy really high-quality vitamin C powder.

MR: How do you know what’s high quality?

MS: Well, you can test it immediately. If you take a gram of this powder that you buy and put it into warm water and drink it, you'll feel it in your brain within seconds. Vitamin C crosses the blood-brain barrier faster than heroin.

MR: Is there anything else you take?

MS: Never forget 400 to 800 units of vitamin E a day, the highest quality vitamin E.

MR: What about exercise?

MS: Absolutely critical. I bicycle every day about 20 minutes on a flat street.

MR: Do you lift?

MS: Very light. I was a zealot in my teen years. I went to the American Health Studios and to the gym on Jamaica Avenue.

MR: Do you remember Daniel Lurie?

MS: I do! Yes, I remember.

MR: Did those ads make an impression on you?

MS: Of course it did. I went and got a set of Dan Lurie barbells.

I had a little attached house in Queens, and it was cold in the winter. My father, who always wanted me to be tough…he didn't like the sensitive part of me — he liked that I was lifting weights in the winter in the basement when it was below zero outside. And he put a rack in the basement for me so I could lift the weights in the garage.

MR: Did you have guns?

MS: No. No one carried a gun in New York in those days except cops, detectives, and gangsters.

MR: Do you carry a gun now?

MS: I've been licensed for 20 years.

MR: What is your favorite gun to carry?

MS: A S&W .357 AirLite PD. It's a small gun.

Bitcoin

MS: You teach law right?

MR: Yes, I teach a class on cryptocurrency like bitcoin.

MS: I'm a total detractor of bitcoin. I know that people hate me for it. But I'm going to tell you what's going to happen — if our fiat currency collapses, they're going to outlaw bitcoin and all of these other coins because they're not going to let private organizations run the economy, period.

MR: Are you a gold guy? Do you like gold?

MS: Yes.

Israel

MR: Did you ever have desire to move to Israel?

MS: Yes.

So I get my Ph.D. in 1978 at UC Berkeley — I have two children. Son is eight. Daughter is two. Nobody would hire me. 80 colleges rejected me. I had a first-rate Ph.D. I had published six books.

The chancellor of Hebrew University, a great man and a well-known scholar — named Rafael Mechoulam. He offered me a fellowship at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. So I traveled to Israel with my wife and two children. I'm ready to move and make aliyah. I was heavily into Chabad at the time.

I get there and I thought I got home to the Promised Land. I remember we got to Israel, and I jumped over the barrier at the airport thinking I was home. And right away, one of the female guards almost put me in jail. It's like my aunt from Brooklyn. So, all right, fine.

I go to see Meshulam, and he says to me, "Look, I can give you a fellowship for two years, but now that I met you, I'm going to tell you something. I don't think you should take it. I don't think you should live here because I see you're a revolutionary, and if you're denied a fellowship after two years, you're going to have nothing. No income here. You'll become a revolutionary in Israel. I don't think it's smart for you to move here."

I go back to the YMCA Hotel — a beautiful hotel in Jerusalem near the King David. I leave my wife and two beautiful children to sleep. I have to think this through. I go for a walk in Jerusalem at night wandering on the cobblestone streets. All night long, I'm walking alone, and walking alone, and I don't know where I was walking, what I was doing. Wandering on the streets of Jerusalem in the Old City.

I hear my deceased father talk to me. And he says, "I was an immigrant in America. Do you want to make your son an immigrant to this country?"

I took the whole family home to America the next day.

MR: If you had to give parents one piece of advice for raising children, what would it be?

MS: Well, it’s not one piece of advice. One you have to love your child almost unconditionally. Yes, be strong. Yes, teach them discipline but do it with love not hatred. Secondly, and very importantly teach your children from an early age how to deal with loss, rejection disappointment, and sadness because they’re going to certainly have to deal with that as teenagers and adults.

After Life

MR: Last thing I want to talk about is the afterlife and death.

MS: Let me let you know about that in a couple of years.

MR: I know you think about it a lot. Does your gut say there's something on the other side or not?

MS: Once, I was walking in the streets of San Francisco and I met a bum, a homeless guy, but not a disheveled bum. He was a street person, but he was dressed well. He had white hair and piercing blue eyes. And I said to him, "Do you believe in God?" And he looked at me with his eyes. They cut right through me. And he said, "Where do you think I came from? Did I create myself?" I never saw him again. I think he was an angel. That answers the question.

MR: You really are a believer.

MS: How can you not be?

MR: What about the afterlife specifically?

MS: You mean, do we go to heaven or hell?

MR: Is there some kind of consciousness beyond this? You seem more sure of God than an afterlife.

MS: I don't have an answer. I don't know. I stopped thinking at a certain point of these questions. I stop it because it can lead only to madness.

MR: Really?

MS: Yes. I don't think every question needs to be answered. We’re only a finite being. We're one of 7 billion people — no matter how big we think our mind is. We're one of 7 billion people.

I carry a book like this around with me — My Gulag Life. Here's a man who went to the gulag just for being a Jew. How did he — an older man — survive in the snow? He had faith in God that carried him through the worst times that you can imagine. So, I think we all have to have faith to survive this world. Especially what we're going through now — watching our country being taken apart day by day by an autoimmune disease where the natural killer cells, which should be protecting us by fighting foreign invaders, have turned on the healthy parts of the body. The left-wingers are the natural killer cells that have gone awry and turned on the body.

MR: How does your Healing Wheel Society fit into all of this? What’s your hope for it?

MS: First of all, I'm not trying to convert anybody. The Healing Wheel is based upon the fact that all of the world's major religions are trying to find God and talk to God, and they all emanate from God. Now, I know that Orthodox Jews believe that their way is the only way, and I believe that Christians 100% resent what I do. They say, "No, you're wrong. Jesus is the only way.” They all say that their religion is the only way. That's my whole point of the Healing Wheel Society, which is — can't we all get along? Can't we all accept our brothers who look different from us? The Jew in the black clothes, the Christian with the cross, can't they shake hands and say, "Okay, same corporation, different division."

MR: And how do you want to do that?

MS: I created a group called The Healing Wheel Society. Its mission is to “lower the enmity between religions and peoples…to emphasize that many religions have more in common than in division. As long as a religion has a belief in God and doing goodness to others, it is part of The Healing Wheel Society.”

It's such an important step for me to go into. It's called Life After Politics.

MR: What do you actually want people to do with it?

MS: Wait till you see the site. You're going to love the site.

Do you see the different people I put up? From Krishnamurti to Billy Graham to Henry Miller. Why would I put Henry Miller and Jack Kerouac on the same page with religious figures? They were mentors of mine in reading.

The Healing Wheel

MR: But do you want people to be more into their own religion because of this?

MS: 100%. What I said was go back to the religion of your grandparents.

MR: Is there any chance you're going to do that?

MS: I have. I'm a Jew.

MR: But is there any chance that the dogma will become interesting again to you?

MS: No. It's too archaic. So when I read the prayer book and it thanks God for giving dew and making corn grow, I can't get into it. I'm sorry. But I understand it's a metaphor because when I was broken in my 40s with two children and no one would hire me, I almost went insane. I went out on a balcony.

You want to hear about my religious conversion?

MR: Of course.

MS: I was living alone with the family in a house in Fairfax, California with Nazis around me, basically. Nazi Leftists. And I was lost. I was lonely. I was wandering in a valley alone. I put on a tallis and I went on the deck and I screamed out to God. It resonated. I gave a geschrei across that valley, and I begged God to save me. I begged God to save me, to give me a job. I said, "Just give me a living. That's all I'm asking you. Don't let me die. I've worked so hard." Within a few weeks, I found what I was looking for. It was talk radio. I know God answered my prayers that day.

MR: And this is my last question, but just curious. There's no universe in which you ever move back to New York City? Or the New York area?

MS: I miss it a lot. Does it exist?

MS: But the New York of my dreams. Is it still there?