Interview with Tobi Kahn

Photographer: Joshua Allen Harris.

Tobi Kahn is an artist.

Mama, Don’t Take My Brownie Starflash Away

Contents

Max Raskin: I wanted to start with the process of turning a creative thought into something real. How do you turn an idea into something that you can remember? Do you have a sketchbook?

Tobi Kahn: I was a photographer as a child — I always drew, but my primary way of thinking was through a camera. At the age of six, I told my mother I wanted to be an artist.

MR: Do you remember your first camera?

TK: It was a Brownie Starflash.

When I was eight or nine, I took a picture with that camera. Years later, it became the banner for the Leo Baeck Institute’s show, Refuge in the Heights: The German Jews of Washington Heights, which ran from 2020-2022.

I was always interested in what most people wouldn’t notice. For instance, I love — not like — the brick wall behind your head. My ideas come from everything I see. I remember sitting in my childhood bedroom in Washington Heights on a rainy day and looking at the brick wall across the street. My mother came into the room and asked me what I was seeing. I told her that I was riveted by the color changes in the brick from when it was dry to when it was wet. She sat down next to me and said she had never thought of it. Her validation encouraged me to become an artist.

MR: So you think in terms of the camera and remember things visually?

TK: Always — and now with the camera on my phone.

MR: What's been your favorite camera of all time?

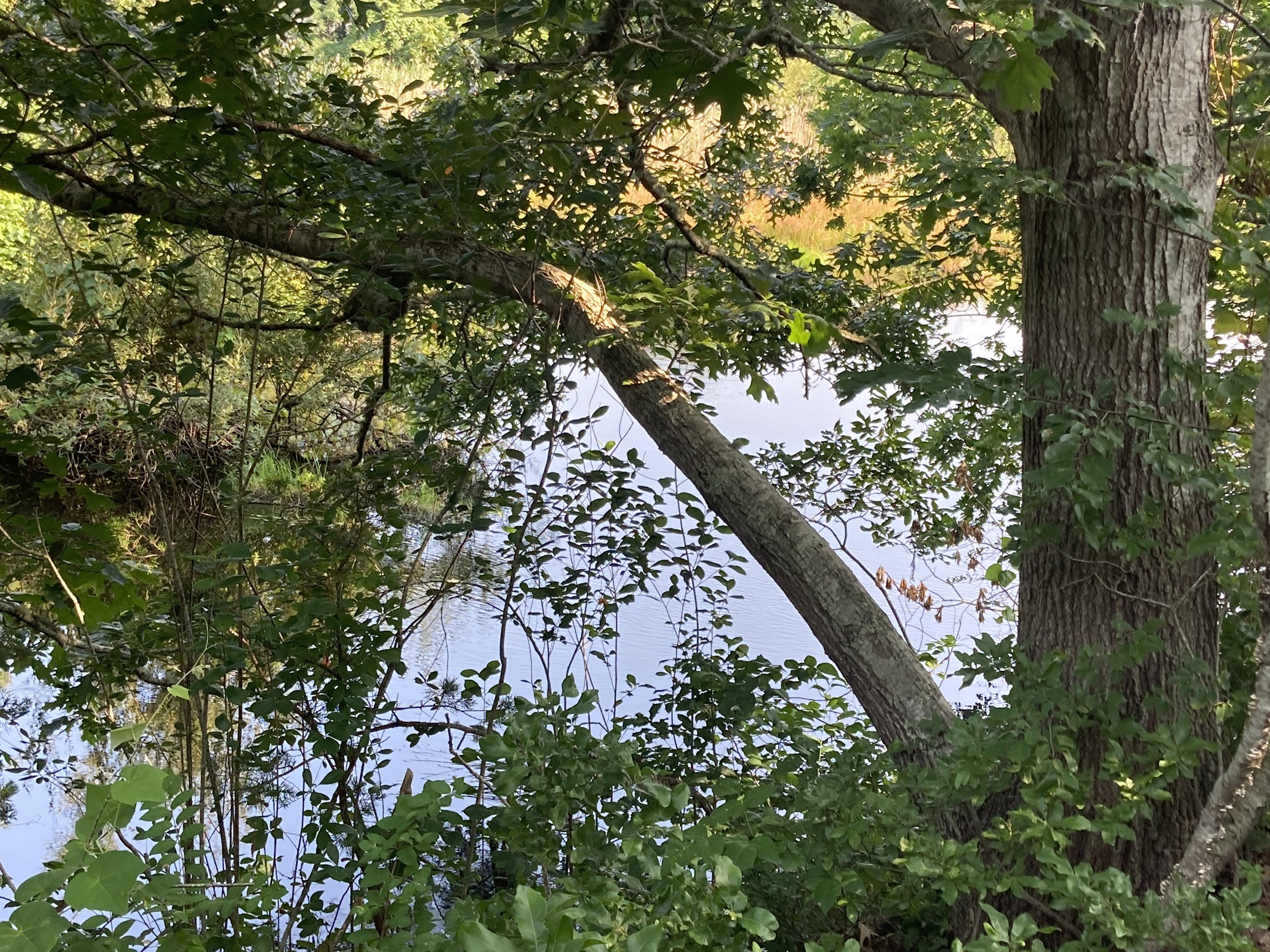

RIFA, Sky & Water installation, 2011

TK: Depends on the year: At times, I loved Nikons, Cannons, and later a Rolleflex. I’ve used over a dozen different cameras.

MR: Did you have a particular model you liked?

TK: Not really. As I got older, I realized I was more interested in what the photograph evoked in me than in the technicalities of lenses and camera models.

What do I mean by that? Today, my most recognized images are my Sky & Water paintings. All my paintings begin in photographs, but if I copied the photograph exactly, I wouldn’t capture what my recollected memory made of what I saw then. I also wouldn’t be able to stir in viewers their own memories of sky and water — which is the reason I make them.

MR: And so the camera is your sketchbook?

TK: Yes. The way I create a painting and most of my sculptures is first by taking a photograph. In my early years, I used to print the photograph in black and white, and then block out anything extraneous with black, white, and sometimes ochre paint. All that remained was the image I chose from the image I’d taken.

In the past 25 years or so, I take the photograph, upload it to my computer, and start isolating through Photoshop everything I don't want in the final image. There are several curators who have wanted to exhibit the original photograph next to the finished painting. I'm not sure I am ready to do that.

MR: I could see both arguments.

TK: The reason I am not sure is that I don't want it to be like Where's Waldo?

MR: How do you mean?

TK: I would lose some of the mystery and leave less to the viewer’s imagination. Since the mid-1980s, I’ve been photographing sky and water imagery with varying horizon lines, turning them into painting installations of different scale, color, and proportion of sky to water. In recent years, I’ve created large painting installations of over 30 images, all of which have the same horizon. There have been many solo museum exhibitions of my Sky & Water series of paintings.

Iceland photograph

FLJOTIR, acrylic on canvas over wood, 2019

MR: I think Giacometti said something like a good portrait looks more like the person than the person himself. I think your paintings are better than the reality.

TK: That’s my hope.

The Magician and His Secrets?

MR: What kind of sketchbook do you use?

TK: I use any paper I have on hand at the time.

MR: You’re not a feinschmecker about your sketchbook?

TK: No. I'm fastidious only about the images I take and the finished work. Most of the time, the sketch is a stand-in; I see something but don't have my phone, so I draw on any piece of paper I happen to have.

MR: And are you fastidious about the kind of pencil or pen you use?

TK: Yes, I use only a soft pencil, usually No. 2.

MR: And how do you store your images?

TK: All the images will be stored on the computer. I have an assistant who is digitizing everything.

MR: How do you file things? Do you do it according to date or something else?

TK: There are named folders on the computer: Cape Cod, Maine, Canada, and many other settings; Dancers, Abstraction, Ceremonial Objects, B&W studies, etc.

KRAULUR, black and white, 2019

Maine photograph

KRAULUR, acrylic on wood, 2019

LSTYN, acrylic on handmade paper, 2023

Landscape photograph

Landscape initial Photoshop image

MR: Is the file according to location or date or something else?

TK: Location and date. Originally, I didn't think about the date, but after decades of working, I realized that I see landscapes differently over time, even if the setting is the same.

MR: Do you feel it’s like a magician revealing his secrets though?

TK: Not at all. Right now, I don't want to exhibit the photographs alongside the paintings, since they are only the beginning of my process. I’m interested in the memory of what I see as well as the memories that are elicited in you. I want to leave enough space for your imagination, so that when you stand before a painting, it is also about your history and memory rather than only mine. I don't believe a work of art is complete until the viewer sees it.

The titles of my work are deliberately not descriptive or even English. My wife, the writer Nessa Rapoport, names all my works. The titles bear the same relationship to language as my paintings do to the image in the world that stimulated them. I so admire Giacometti’s work and what he said about sculpture — that he is more interested in what he takes away than what he leaves. I want to give only as much information as viewers need to correspond to their reality. I never want to dictate their response.

MR: Let me ask a flip side question. My understanding, and I could be wrong, is that all the great conceptual artists had training as non-conceptual artists.

If you gave me a pencil and said, draw a picture of a person, it would look ridiculous. You could give me 20 hours and I could sit and it would not look like anything.

I don’t know if this is cheeky, but do you have chops as a non-conceptual artist?

TK: If you mean, can I draw naturalistically? I can, but it doesn’t engage me.

Let me tell you about my education. I went to Jewish day school from kindergarten through 12th grade. I always made art, and then I studied acting in university for one year and went to yeshiva for three. I earned my BA from Hunter College, majoring in photography and printmaking, and attended Pratt Institute for my MFA in painting and sculpture.

MR: What yeshiva did you go to?

TK: I studied at Yeshivat Kerem B’Yavneh for one year and Yeshivat Har Etzion for an additional two years.

In all these settings, I was always thinking and learning through an artist's eye. In fact, I teach a course at the School of Visual Arts called “Visual Thinking.”

MR: Can you turn that faculty on and off?

TK: It's always on. Even on Shabbat, the only day of the week that I’m not actually creating art.

MR: What about when you're watching something stupid on TV?

TK: I still notice everything — fake backgrounds, toupees, minor actors I’ve seen before, lack of continuity in furnishings or landscapes.

When my wife and I walk down the street, she often asks me what I’m seeing. I can tell instantly when couples are in communion, or people are overjoyed, angry, or in a bad mood. When I am teaching, I notice immediately when students are distracted. Tons of visual information is constantly coming at me.

MR: But is it exhausting?

TK: No, I find it exhilarating. Except when I encounter bad people, even before I say a word to them. That’s painful, because I know.

MR: This is how you said you construct your art — you like to take away all the information that you don’t think is relevant.

TK: Right, my brain works that way. I pare down what I see to the essence.

Being Artsy Versus Making Art

MR: Where's your t-shirt from? And the rest of your clothes?

TK: My t-shirts are Jockeys. My jeans are black Levis. On Shabbat, I wear a Charles Tyrwhitt white shirt and black pants. During the winter, I wear Patagonia black down jackets. This way, I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about what I’m wearing. In art school, I had an extraordinary teacher and mentor, the artist George McNeil, who said: “You can spend your time either looking like an artist or making art.” I made a decision then that I’d have a uniform so that I could spend as much time as possible making art.

What’s most important to me is to create art that adds healing beauty to the world; my wife, children, grandchild, sister, family, friends, and students; and my belief in God, which underlies everything I do.

Potato Salad Triptych

MR: Are you a feinschmecker about anything besides art?

TK: I love cooking. We often host a large crowd for Shabbat lunches. On Thursday nights, I cook enough food for that lunch and for most dinners of the week to come.

MR: What's your go-to dish?

TK: My wife says one of the reasons she married me was my potato salad.

MR: Tell me about the potato salad.

TK: I make three different kinds.

MR: Can you tell me about one of them?

TK: For the one that's based on my German-Jewish upbringing, I use Yukon potatoes. I boil them, and as soon as they're boiled through, I let them cool and cut them into chunks. Then, I add olive oil, garlic, scallions, Italian parsley, and shallots. I cook them in a skillet until they’re brown. Last, I sprinkle sea salt and pepper, and sometimes a dash of soy sauce.

There is another version with a lemon-and-oil vinaigrette. I love potatoes.

MR: Does taste mean as much to you as visual?

TK: One doesn't work without the other. They're equally important.

MR: Are you a synesthete?

TK: No, but I do care about how my food looks. I won't eat anything that doesn't look appealing. So it’s taste and appearance.

MR: I want to ask you about sound. Do you listen to music when you make art?

TK: Yes, all the time.

MR: What's the last thing you listened to?

TK: Piaf, late last night.

MR: When you’re creating your art, what type of music do you think you’ve listened to the most? Classical? Jazz?

TK: One of my closest friends, the art historian and curator Douglas Dreishpoon, who is also a drummer, says he can tell on the phone what stage I’m at in my painting by the music in the background. I never thought of what I was listening to at a given time until he said that. It’s classical music in the early stages of my work and jazz during the final glazing process.

MR: Where do you mostly shop?

TK: Costco. I shop there almost every Thursday in the late afternoon for most of the food and supplies that I use for our Shabbat lunches. I started going to Costco 20 years ago, after my mother died of pancreatic cancer six weeks from diagnosis. When I couldn’t concentrate and was throwing up, I called a therapist friend of mine and told her my symptoms. She knew I was very close to my mother and said that what I was experiencing was the grieving process. She suggested I do something that my mother had always wanted to do with me — but we hadn’t had the chance.

My mother always wanted me to join her at Costco, and that’s how the store became a part of my life.

Kids Say the Darndest Things

MR: What’s the most common question you get asked as an artist by the average person on the street?

TK: They ask me what you asked me: Can you draw? And the answer is yes, but I don't find the question relevant. Famously, the figures of one of my favorite artists, Cezanne, were not always anatomically correct, yet his paintings are breathtaking.

MR: But can you draw?

TK: Yes, I can. I'll tell you a powerful story about my daughter. Every year in the spring, we have Bring Your Child to Work Day. Since I teach a painting class at the School of Visual Arts, I took her along. As I walked around the classroom, students were asking me how to improve their work, so I did multiple demonstrations.

My young daughter said, “Wow, Dad, you can draw anything.”

I said I could.

“So why don’t your paintings look more real?”

I answered her, "They show what interests me.”

MR: So best friend’s mom growing up was an artist named Jessica Lenard, and she was also my mom’s best friend. My mom tells this story of when I was seven or something and I met her for the first time. My mom says, “This is Jessica.” And I said, “What does Jessica do?” She said, “She’s an artist.” I said, “Yeah, but what does she do for a living?”

L'art Poor L'art

MR: Do you think about money?

TK: I don't think about money for money’s sake. I do think about how it’s necessary for me in order to live my life. I wanted to send our children to Jewish day school, summer camp, and pay for their university so that they would be debt-free on graduation.

Knowing that I would need a steady income, I always taught art. I started teaching at a Sunday school when I was 13. While I was studying art in university, I taught at a Jewish high school, at senior centers, and at after-school art programs.

In 1985, when I was one of nine artists chosen for the exhibition, “New Horizons in American Art,” at the Guggenheim Museum, everything changed. Since then, I continue to teach at university, both because I love teaching and because I always want to have a base of income, in case. My teaching at SVA has also been the source of all my wonderful assistants, who were my students first or were recommended by other faculty members.

Money interests me only when it enables me to continue making art and to help support my family.

MR: With my interviews, I think the ones that get the more hits maybe they’re better. Do you think that way about your pieces?

TK: I'm not driven by the marketplace, because I have amazing and committed collectors. Some have been buying my paintings and sculpture consistently for over 30 years.

People buy my art because they love it. Thankfully, they almost never sell it, but often, after time, they donate pieces to excellent museum collections.

There are also many curators, museum directors, and art historians who are very supportive. I’ve had 70 solo museum exhibitions, and my paintings and sculpture are in over 40 museum and public collections. Collectors and curators come to my studio regularly.

ALOMH

I work on several projects at once, from large commissions to works on paper. This year, I completed a 25-foot meditative sculpture for the Honickman Center at Jefferson Health, in Philadelphia. I have installations of outdoor sculpture and meditative spaces throughout the country.

What thrills me is that people are interested in seeing my work and living with it. I’m obsessed with making art; it’s all I’ve ever wanted to do.

MR: Do you have a super fan?

TK: I am blessed by all my collectors. Early in my career, Herb and Dorothy Vogel, major art collectors, bought two of my paintings. Dorothy was a librarian, and Herb worked for the postal service. They loved art for all the right reasons and would pay small amounts over years to artists whose work they admired, amassing one of the most amazing collections, whose pieces were later donated to many museums. There is a wonderful film about them called “Herb and Dorothy.”

The person who changed my life was Jane Blaffer Owen, of the Blaffer Trust and the Blaffer Museum in Houston and New Harmony, Indiana. In 1993, Jane saw a small sculptural shrine of mine at MoCRA, the Museum of Contemporary Religious Art in St. Louis. From then until her death, in 2010, she was my greatest patron and a beloved friend.

Jane commissioned many works, including Shalev, an outdoor sculpture for New Harmony, a 45-foot Sky & Water painting now at Rice University, and several others. She, too, donated many of my works to major museums and funded solo museum exhibitions.

MR: Do you think she understood what you were trying to do?

TK: Definitely. Jane was a devout Christian, and she understood my belief in God in a deep and powerful way. I loved creating art for her.

Many of my major collectors are people of faith.

Faith

MR: Have you had waxing and wanes of faith?

TK: No. If somebody I'm close to dies, I'm devastated. And when there are terrible things happening in the world, I feel crushed. But I've always believed in something larger than myself.

I also have to be clear in saying that I don't believe there's only way to God. I happen to be an observant Jew and I am proud of it.

MR: As John Sexton would say, you're not a triumphalist.

Ceremonial Objects — Seder Plate

TK: Correct. I love John. John and his amazing late wife, Lisa Goldberg, have been incredible supporters of my work. He studied at a Jesuit school, which he said was a great influence on him. I've worked with two Jesuit priests who truly understood my art and why, as a religious person, I am an artist. Both commissioned large projects over the years. In fact, I met Jane Blaffer Owen through Terry Dempsey, a Jesuit priest who did his doctoral thesis at Berkeley on artists of faith and later founded MoCRA.

Terry also introduced me to his professor at Berkeley, Peter Selz, a brilliant art historian and curator. Peter went on to curate three solo exhibitions of my work, one of which, Metamorphoses, travelled to eight museums across the country.

Ceremonial Objects — Omer Counter

I create work for many reasons and occasions, including birth, marriage, synagogues and interfaith spaces, Holocaust memorials, hospitals, and hospice installations. I just finished a project with the last two pieces of steel from 9/11, which I was honored to receive from the Port Authority/MTA. From these relics, I created memorial lights in an edition of three bronzes. They are now at the 9/11 Memorial Museum, NYU’s Grey Art Museum, and the Trinity School.

I also have a body of ceremonial art that I’ve been making continually. These works have to meet three criteria: They must be beautiful; functional in terms of their ritual purpose; and fulfill the stipulations of halakhah, or Jewish law.

In 1999, Carol Brennglass Spinner and I founded Avoda Arts, a nine-year project that included a traveling museum exhibition of my ceremonial objects and an educational program for which I taught thousands of college students how to make ceremonial art from their own faith traditions.

Relentless After Breakfast

MR: You are relentless about your work. You’re doing what you’re supposed to be doing.

TK: From a very young age, I knew that I was placed on this earth to create art. I don't like the word relentless, but I am very committed to my artistic practice. You have to pull me away.

MR: You will not relent.

TK: I am also a passionate educator. I want my students to find their own voices.

MR: For someone who has never done anything artistic whatsoever in their life, if you could give one recommendation of either a class to take or a medium to try out to explore that side of them, what would it be?

TK: I don't believe art classes are the only way, even though I'm a professor and love teaching. But I do believe in helping people open their eyes. I want you to slow down and look around. I believe visual thinking is just like learning a foreign language: It’s a different mode of perception and expands your capacity for joy. I find it very sad that so many people don’t know how to see.

If you want take a picture of a famous site or make a painting, do you want to include only the site? Do you want to see yourself in front of it? Are you more engaged by its outline against the sky or by what is happening on the grounds around it? What is interesting to you?

MR: What do you usually have for breakfast?

TK: I always have the same thing. Half a bagel, a sunny-side up egg, avocado, tomato, and olives.

MR: And what do you drink in the morning?

TK: Water, a lot of water, and sometimes decaf coffee with almond milk. I can't have caffeine. In case you haven't noticed, I'm very intense.

MR: Do you sometimes have to set an alarm, so you don't forget to go home from the studio?

TK: No, I watch the clock. I'm happily married, and that is a priority, so I am very conscious of the time. But when Nessa is out of town, I work in the studio ridiculously late.

MR: Would you sleep at your studio if you could.

TK: When I was younger and single, I did, regularly. However, after I got married, I realized that having a studio away from where I live was essential for my family life.

MR: You don’t need to unwind?

TK: No. But I’m delighted that Shabbat comes every week; that is the one day I truly do relax. Since COVID, Nessa and I have been watching British murder mysteries most weekday evenings. We’ve seen dozens.

MR: Are you just zoning out watching or is your brain in artist mode?

TK: I am constantly trying to figure out the story behind every character.

MR: But you're not looking visually at it and going crazy?

TK: Even as I'm absorbed by the plot, actors, and structure, I’m always asking whether the background is real. Was it filmed in a studio or on location? Did they do it in one take or many takes?

MR: And what about exercise? Do you do anything for exercise?

TK: My studio is on two floors, and I'm going up and down the stairs constantly. I used to bike. For years, I biked everywhere.

MR: Why did you stop?

TK: I stopped because of COVID and haven’t gotten back to it, but I hope to soon. Now I drive to the studio two or three days a week; the other days, I'm on the subway. I have so many things I have to think about. On the subway, I have my paper calendar, and I write down what I'll be doing each day.

MR: What does it say?

TK: “Meet so-and-so, see exhibitions, give lecture, do this and that, and respond to emails and phone calls.”

MR: What brand of brush do you use? Do you care?

TK: I have hundreds of brushes of all different sizes and shapes.

MR: And you don't have a favorite brush?

TK: It depends on what I'm working on. If you go to the other room, you'll see brushes of every size. What I use depends on what the piece needs. A very thin brush? A square brush? A round brush? A Filbert brush? A very thick Japanese brush?

I do like bristle, but at times I need a very fine sable brush. And other times, I will use a very fine synthetic brush. And sometimes, I have to customize a brush.

There’s no formula or shortcut. There's no “how to make a Tobi Kahn painting.”

Cataloging

MR: Are you fastidious about cataloging your work?

TK: I’m lucky to have outstanding assistants. Everything is now being cataloged — everything. I have somebody who answers my email. I delegate whatever doesn't need my artistic attention. I don't build, stretch, gesso, or sand any of my surfaces anymore. And I no longer wrap and prepare work for shipping.

But I do mix all my own paints and add multiple layers of glazing to each painting. When I finish a painting, sculpture, or ceremonial object, I have a photographer come in to document each piece.

Here is the file with images of all the paintings that are going to different exhibitions.

MR: That's interesting that it's in hard format and not on the computer.

TK: It’s on both. I use the computer because it allows me to organize my work chronologically and to house all the iterations of the work I create. But I like paper. I like seeing. I still keep index cards with the original drawings and the data on every piece. I'm not going to get rid of them.

When I travel, I take many photographs, some of which eventually become a series of paintings. A few weeks ago, I took over 100. I’ll show you what caught my interest.

MR: And you use an iPhone?

TK: Now I use only an iPhone. I don't delete almost anything, because I want to remember what captivated me at the time.

MR: You must have the highest subscription on Apple’s storage plan.

TK: I have no idea.

Look at these images. They are all ideas for future work.