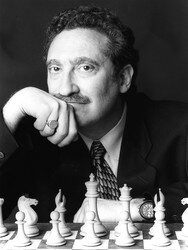

Interview with Bruce Pandolfini

Contents

Bruce Pandolfini is a national chess master, world-renowned teacher, and consultant for Netflix’s The Queen’s Gambit. He was an analyst for PBS’s coverage of the 1972 Fischer-Spassky Match.

The Queen’s Gambit Gambit

Max Raskin: Did you ever play chess in Washington Square Park?

Bruce Pandolfini: Sure.

MR: When did that become a thing?

BP: That was always a thing – even in the 40s and 50s. I wasn’t around then but I know that for a fact.

MR: Do you ever go to the park now to play?

BP: Not really. I’ll walk through the park to see what’s going on. Sometimes I’ll meet people there or we’ll do interviews. Some of the park players are pretty good, by the way.

MR: You talked once about what Shelby Lyman would do when he taught a new student.

BP: It was Shelby who encouraged me to be a chess teacher. Back in 1972, he said he’d like me to maybe take over some of his students and I said, “I’m not a teacher. I’m a very bad poet.” In those days, I wanted to be a poet like Allen Ginsberg or Dylan Thomas. I was working at the Strand Bookstore. In fact, I was one of the organizers of their union – Local 65 – which the Strand owners never quite forgave me for.

One day Shelby asked me to come along with him because he was giving a lesson to a new student. So we got to this guy’s apartment, with a chessboard and pieces already set up. The lesson starts, and Shelby, sitting with the black pieces, said to the fellow, “move.” And the fellow said, “I don’t know how the pieces move.” And Shelby said, “Move them the way you think they move.” I really thought that was profound. Not that the guy could divine how to move the pieces. But in trying to move them, he would be so much more receptive to picking the moves up once they were shown. A valuable groundwork or foundation was laid by that.

MR: I think that’s one of the most profound things I’ve ever heard.

BP: He was a brilliant guy. He was the chief analyst for the PBS coverage of the Fischer-Spassky match. I was also an analyst for it, but I had a marginal role. Shelby was an extraordinary man. He did it brilliantly, and he had a likeable on-screen persona – very articulate and you could identify with him. In fact, millions of people watched that coverage without knowing much about the game because they found it so engaging. We were all thankful for Shelby Lyman.

MR: Is that how you feel about The Queen’s Gambit?

BP: Its outreach and how it’s drawn people to the game? I think it’s a great thing. I was also involved in the publication of the novel originally.

MR: Someone told me the title comes from you?

BP: The title does come from me.

I had read the manuscript that Random House had sent me, and I met with Walter [Tevis], the novelist, and his editor, Anne Friedgood. I told them what I thought was right and what was wrong about the book. Overall, I liked the book very much. I thought it was very timely to have a female chess heroine. They liked that, but I said there were some problems with the chess in the manuscript, and it seemed some details should be changed. Walter didn’t like that idea because he was a chess player already and was very proud of the chess he had put into the book. Plus, he was a writer – he didn’t want to have his prose interfered with. I also think he was fearful of having to pay me something.

MR: But you did give him the title?

BP: Yes. Once it was clear that we weren’t going to go any further, and as I was getting up to leave the office, I turned to them and said, “By the way, your title is not quite right.”

MR: Do you remember what the title was?

BP: It had the word “Queen” in it, but it didn’t especially hit the nail.

I said, “You know, it should be the Queen’s Gambit.” At this point the chief editor at Random House said, “Wait a second, let’s talk some more.” That got me back into the office and a half hour later I was the consultant on what would thereafter be called The Queen’s Gambit.

MR: Did they pay you?

BP: They paid me handsomely for those days.

I met with Walter maybe 10 to 12 times in his brownstone. He was an interesting guy. All kinds of things happened while I was there. By the end of my time with him, he agreed that he would make many of my suggested changes. But he didn’t.

He liked certain terms and names. For instance, he had a thing for the Levenfish Variation. He loved the sound of that name. But it made no sense in context. It doesn’t matter though. When you’re reading a passage of moves, you might not visualize them too well, so the writer can get away with metaphorical stuff. But on screen it has to be accurate because the audience can see it. You can’t say a rook moves when it’s a bishop that moves.

MR: Someone should create a game called “Genetic Disorder or Chess Move?” You know like, “Oh, that’s the Hodgkin’s Lymphoma – e4, e5, d4.”

BP: Believe me there are many with such appellations – unexpected, wild names, such as the Frankenstein—Dracula Variation, or the Dragon Variation – so named because the outline of the pawn skeleton looks like the winding tail of a dragon. It helps to have a vivid imagination.

MR: It’s like constellations.

BP: Yeah, it’s like that.

MR: Three dots – oh yeah, that’s a belt…Orion’s Belt…yeah, I don’t think so.

Bloomsday

MR: What percentage of the books behind you are chess books?

BP: A lot of them on that wall have to do with chess, but I have many other kinds of books too. Heck, I have five storages around town.

MR: How do you organize your books?

BP: Randomly. They’re not very organized at all. But I tend to know the shelves where particular volumes are, though it’s getting harder.

MR: How do you read books? Digitally? Hardcopy?

BP: Both. I also listen to books now – audible.com. That can be quite enjoyable.

MR: What’s the last book you listened to fully?

BP: Fully? Ulysses. Actually, it’s one of my hobbies. It’s my nineteenth time going through Ulysses. I’ve read it the first eighteen times and the last time I actually listened to it.

MR: Wasn’t it just Bloomsday?

BP: June 16th.

MR: Do you celebrate?

BP: In one way or another. I’ll at least have a drink.

When I was 17, I met an authority on Joyce and Ulysses from the Marshall Chess Club. He introduced me and a few other club members to it. The first time I read it, I got very little out of it. I forced myself through it as much as any 17-year-old might do. But with subsequent readings through the years, I think I've learned a few small points about it. I won't pretend to be an expert – I’m not. But I always enjoy doing it.

MR: I could never get into it.

BP: It’s part of my craziness.

MR: How did you push your way through it?

BP: I just self-willed it. I wanted to do it – maybe it was simply to prove that I could do it. It’s so far back. I’ve certainly derived much pleasure from the book over the years. Before that I had read Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which initially I also didn’t get a lot out of even though it’s easier to read. And then soon after I read Dubliners, which is much easier. By then, I had become a Joyce fan.

MR: When you celebrate, what do you drink?

BP: I’ll probably go to Irish whiskey.

MR: Do you have a favorite?

BP: I can’t say I do – I do experiment though.

MR: Are you a feinschmecker of any alcohol or food?

BP: No, my tastes aren’t that refined. I’m fairly omnivorous across the board in what I eat. I try not to eat anything ridiculously bad or problemsome.

MR: Do you snack during the day?

BP: Sure, it's hard not to especially when you visit students – they put snacks out. I try to resist their temptations.

MR: If you had your druthers what would you snack on?

BP: I like salty things more than sweet things, and I wasn’t a chocolate fan when I was younger, whereas most people are. I was a vanilla and a strawberry fan. But I’ll eat chocolate now.

MR: What kind of chocolate?

BP: Dark chocolate.

MR: Do you like it very dark?

BP: Not very dark, but 50-70%.

MR: Some people like the 90% stuff.

BP: I’ll eat that, I won’t turn it down.

MR: What about coffee, do you drink coffee?

BP: I used to drink quite a bit of coffee. Now I only drink in the morning to get going.

“My Mother Thought So…”

MR: Do you think most great chess people are well-rounded?

BP: You know, first of all, let me say I am not a great chess player. I'm a decent chess player.

MR: You're a great chess teacher.

BP: Well, my mother thought so. I'm an experienced chess teacher. I possibly have logged more teaching hours maybe than anyone. This is my fiftieth year teaching chess.

Trying to address your question, I would think that some top chess players are interested in ideas, and “great writings,” but not all. You have to be monomaniacal and really focused on your chess if you want to reach the top. You’re up against other geniuses, and really, whoever works harder, and puts more into the effort may get a slight edge on everyone else. But no matter how gifted you are, it's not going to be an easy ride. It’s really true – there’s no royal road to learning.

MR: Because you seem like such an interested person, is it hard to be around people who are not?

BP: Well, you have to hold back. Because if you start throwing this and that out, they won’t know what you're talking about, and you'll lose them fairly quickly.

MR: Do you think if I took a lesson from you, we would end up kibitzing?

BP: I try to control that. I really try to get across what I think the student needs in that hour session. But I would expect at least a little kibitzing.

People always ask me, is there any one thing you have to do or learn to get going in chess, and really, there's no such thing like that. You can learn in many different ways. I could give you a piece of advice that's worked many times for other people that would have no value to you. Or I can suggest something that is absurd on the surface that may have great value to you. I really do try to treat everyone as an individual and learn something about them before proceeding. To that extent, I'll pose many questions to unearth and elicit information about them so I get a sense for who they are.

Teaching with the Third Ear

MR: I read somewhere that you’ll ask hundreds of questions in a session.

BP: That does happen, even to the very young, because the questions are integrated into the conversation. They don't even realize some questions are questions.

MR: You said you read Freud.

BP: I must have read fifty things by Freud.

MR: Did you ever formally study psychology?

BP: No, my degree is in physical chemistry. Maybe minored in philosophy and English – I was all over the place.

MR: Where did you go to college?

BP: All over the place.

I barely got into college – I was a terrible student. I was one of the New York City's worst truants back in the old days. But I wasn't doing drugs on the corner, I was doing my own thing, chess, reading, whatever.

I don’t know how I got through college. I did a year of graduate work too – then I dropped out.

MR: There’s a great book I would recommend called Listening with the Third Ear by Theodor Reik. He was an early student of Freud’s and wrote about using your unconscious to understand a patient, or, in your case, a student.

BP: I don’t know how it evolved as an approach or method for me. It was no doubt inspired by my readings. I won’t say I have any original ideas.

MR: How much do you read? Do you still read a lot?

BP: When I can. I have to do it while traveling or being on a subway because I just don't have the time.

MR: Is traveling annoying to you?

BP: I’m kind of used to it – I don't think about it much. It’s hard to do things while standing on a moving vehicle, especially during these pandemical times. It's starting to get more crowded again and there’s crazies on the subway. But even other modes of transportation are not so pleasant necessarily.

I really yearn for the opportunity to read anything. I haven't read many of the items in my library – certainly not fully. But I've always tried to touch upon everything I’ve put on my shelves. That's certainly true for chess books. You don't read chess literature all the way through. You tap it for the examples you want – for the ideas here and there, the reinforcement. Chess writing is not real writing anyway.

Simultaneous Reading

MR: How many books will you read at a time?

BP: Well, I often slip into reading multiple books simultaneously. I do try to limit that because you can lose the thread of each one. But also, it's a challenge – you know, how many things can you keep in your head. When I trained myself earlier in life to be able to play multiple games of chess in my mind, that was a technique I tried to adapt for other activities as well.

MR: Do you read when you’re in bed?

BP: Not anymore – I used to. I would always find times to read, in and out of bed.

I got interested in philosophy when I was working at my first job, which was at the University Place Book Shop around 10th Street and University Place in Manhattan. I was cleaning out the basement – I think I was fifteen – and I came upon this book by Bertrand Russell called Political Ideals, which was his first book. It was dusty, and I looked at it and became very excited. I started reading and it took off from there.

He was also one of the most intelligent people I've ever encountered on any page. I love his writing style and love his thinking. I'm not sure everyone loved him. But I love Bertrand Russell.

MR: He was a real atheist – with the teapot. Are you religious?

BP: No, no, I'm not religious.

MR: Were you raised with a tradition?

BP: Well, I have both a Christian and a Jewish background. And both of them were in the air. I grew up in Borough Park, Brooklyn, which became a heavily religious Jewish area. I think it became that way in the mid-50s. It wasn't beforehand – it was a mixed area before then.

MR: Did you ever formally study how to teach?

BP: I looked into established educators – I think of myself as trying to be part of a tradition going back thousands of years – including the Greeks.

MR: So you read about education?

BP: Yes.

MR: Who’s the first educator that pops into your mind right now?

BP: Socrates.

MR: What’s the first chess opening that pops into your mind right now?

BP: The King’s Gambit.

Capitulation and Recapitulation

MR: I always ask these questions and people think there’s a right or wrong answer, but whatever pops into your head is the right answer.

BP: I'd have to harmonize with that, but there's a reason you go somewhere to start with. You’ll see something analogous to that in chess thinking. It’s not always easy to formulate a plan, which is best done on your opponent's time. On your own time you have to get very specific – your clock is running. On your opponent’s turn you can pose more generalized questions to focus on weaknesses and find targets to attack. And one of the questions that's usually posed is, “what would I like to do if I could?” That's a ridiculously generalized question – we call that Capablanca’s question. Unconsciously or subconsciously your mind will be led to something relevant by just posing that blanket query. Even if it doesn’t get you to the right place, it’s likely to be germane to some extent.

MR: I read a book about Lasker saying a similar thing.

BP: Well, he was a very interesting man.

Einstein wrote the foreword to a biography on Lasker. It's very curious, because they were friendly acquaintances. And he said some nice things about Lasker in the intro. But then what does he do for the entire foreword? He addressed Lasker’s criticism of his theory of relativity.

It’s fascinating – Lasker had the following objection: you say the speed of light is constant and everything hinges on that. How do you test that? Since there's no perfect vacuum in nature, how do you know that the speed of light wouldn't be infinite? What did Einstein do in response to that? He said, “Well, we can’t know – but if we think like that we’ll never get anywhere.” And so you see the difference between the scientist wanting to explore and try things – we don't always think of scientists that way. The difference between them and chess players who think in other ways. Now, it’s not necessarily one or the other. You can have both kinds of thinking in your chess arsenal.

MR: It’s bootstrapping – you just need to posit something. I think of i. It doesn’t make any sense to take the square root of a negative number, and I remember getting very upset when I heard about the concept. But the person who taught it to me explained it has so many applications and you wouldn’t be able to do things in electronics and whatnot if you didn’t have this fiction.

BP: That’s a very good point you raise. It triggers in my mind what one of my math teachers said to the class once – he said something to the effect, “I’m going to show you something now that won’t make much sense and I can’t quite clear up, you’re gonna have to accept it. But by doing so we can go further, and then later on, you'll understand it better.” Now that’s not an easy thing to accept.

MR: There is rabbinic concept that comes from when the Jews accepted the Torah at Sinai – they said, “We will do, and we will listen.” The rabbis pointed out the order is instructive because the thought was you should first act and then you will come to understand. Action will influence thought – it’s not a one-way street.

BP: There’s are reams of profound things in Talmudic writings – they’re incredibly extensive. Not all of it is so relevant or applicable, but there are some really deep nuggets throughout.

MR: What chess book do you think has the best literary qualities?

BP: Very tough call. Most chess writing is not really writing.

MR: I like Nimzowitsch.

BP: Probably the best pure writer of chess English was Fred Reinfeld. I love his The Human Side of Chess.

I also like Nimzowitsch’s writing a lot. He contributed much to chess theory and really changed the game. That's a profound book, My System – many people will cite that as being the best chess book ever written, even though it’s quite dated now. Although what good chess players do in today’s world is not very far removed from what some of those thinkers put forth from earlier times. The game changed with Paul Morphy in the 1850s. A little bit wacko in many ways. His two-pronged approach to chess – taking care of his own needs and handling his opponents’ threats – inspired many people. He really changed the way chess was played but didn’t write about it. It took Steinitz to write about Morphy’s ideas and those who came after him.

You’ll see chess players drawing from the outside world in their thinking. For example, one way to study chess is Réti’s evolutionary approach to chess study. What he said is essentially that the development of the individual chess player recapitulates the development of chess theory itself.

MR: Have you ever heard “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny”?

BP: It’s exactly the same thing.

MR: Quine made a joke about ontology recapitulating philology.

Do you listen to music when you play?

BP: Oh yeah. I listen to a lot of music.

MR: Do you listen when you play?

BP: When playing online – you can’t when you’re sitting with someone.

MR: Do you play online?

BP: Every day. Well, pretty much every day. Speed chess just to stay in shape and for fun.

MR: Where do you play? Chess.com?

BP: Sure, and other offerings.

MR: How long do you play for?

BP: 10-minutes per side. Which is not very fast compared to what you could do.

MR: What do you listen to when you play?

BP: Classical music.

MR: What kind of classical music do you like?

BP: All over the place – from really classical to the romantics to the moderns.

MR: Who’s the first classical composer that comes into your head right now?

BP: Bach.

I like great piano music as well. There I might even go romantic and listen to Chopin or Rachmaninoff.

MR: Is there a piece you really love?

BP: There are many pieces I love. Many that are overly popular.

MR: What’s a popular and an obscure piece you like?

BP: Really popular – Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No.2. Not popular? Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9.

MR: Where do you listen to it?

BP: YouTube or I have various apps downloaded to my phone.

MR: Where do you get your news from?

BP: I might turn on the TV for a few minutes. I don't really look at news on my phone so much.

MR: Do you get a hard copy delivered to you?

BP: The [New York] Times.

MR: Will you look at it every day?

BP: No, just the front page.

MR: Do you do the crossword puzzle?

BP: Very rarely.

MR: Do you do sudoku?

BP: No I don’t.

MR: A lot of chess players like games – do you like games?

BP: I like some games and some puzzles, but I don't really invest any time in doing them.

The Fischer King

MR: There’s a video of Bobby Fischer on the Dick Cavett show solving a puzzle.

BP: I remember that. On several of those shows – Cavett, Johnny Carson – he comes off as very warm and personable. It's only later that you see the craziness coming out.

MR: My joke is that that Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess sold much better than the sequel, Bobby Fischer Teaches Virulent Anti-Semitism.

BP: You can certainly characterize it as true anti-Semitism, but it's also self-hatred.

MR: His mother, right?

BP: His father as well – for years it was not known that his real father was also Jewish.

MR: Both of his parents were Jewish?

BP: Yes. There's no doubt about it.

In fact, when I was involved in Searching for Bobby Fischer I was going around with the set director, and we had to go to where Bobby Fischer really lived in Brooklyn. We got into the car service and we gave the address and the fellow says, “Oh – Fischer’s address!” He said, “I know it very well – his father and my father used to go to shul together.” When I told people about this, they couldn’t believe it. He even drove me to the synagogue. Maybe the guy was just inventing it, but that’s what he said. Subsequently, a reporter tracked it down and indeed proved that Fischer’s father was Jewish.

MR: So you knew Fischer?

BP: Oh yeah. I wouldn't have called myself a friend – I couldn't call him on the phone. But I was a friendly acquaintance. I once sat with him for three hours and analyzed chess.

By the way, he did have earplugs on while listening to rock music. At the same time, he was eating a hamburger that he had taken out from somewhere. I was just very happy to be sitting with him.

On other occasions, I did have conversations with him. I was a wall boy in 1963 when he went 11-0 in the U.S. Championship – the only time where there was a perfect score. So I handled five Fischer games. It was incredible. I had the pleasure – and responsibility – of making moves on a demonstration board for the audience to see. Even then, nine years before the Fischer-Spassky match, all kinds of people were excited about Bobby Fischer. For the audience of the Fischer-Reshevsky game, sitting there in the first row were Stanley Kubrick and Billy Wilder. Both were chess enthusiasts.

MR: Who’s someone who you know to be a very strong chess player that most people don't know to be a strong chess player?

BP: Humphrey Bogart was a very strong player – maybe the best in Hollywood.

Marcel Duchamp was a master. I met him several times. He was an intriguing gentleman. I first encountered him when I was ten because my father was an artist and knew him.

MR: Do you know [Magnus] Carlsen?

BP: Yes, I’ve met Carlsen. I’ve sat with Carlsen at a dinner. But I think because I was Fabiano [Caruana]’s original coach he didn’t want to talk to me much.

MR: Do people love asking you what it was like to know Fischer?

BP: Yes, yes.

Bobby Fischer had very few friends. It always makes me laugh when people claim to have had him as a good friend.

MR: What’s the chess set that you go to in your house if you just want to play?

BP: A standard plastic tournament model that you can get from the U.S. Chess Federation. You don't want anything so ornate and distracting that you can’t play chess.

MR: What's the first piece that comes into your mind right now?

BP: A knight.

MR: Why do you think?

BP: They used to call me the Knight Man because I was very good at knight maneuvers. Well, relatively. But I like the knight. It’s also the hardest piece to teach because it’s not linear.

MR: How did you get into chess?

BP: I was about 14, and I knew how to play already, but didn't really know anything. I was in the library in Brooklyn, walking through the stacks, and I came upon the chess section. I didn’t know there were books on chess – I became fascinated. There were 32 books in the section, and I decided I was going to take out a few, but I couldn’t decide which ones. You were allowed six books at a time, as I recall. I did the only sane thing I could think of – I went back six times and cleaned out the entire section, and I didn’t go to school for a month.

MR: Do you nap during the day?

BP: No, although I’ll find myself getting more tired recently. I sleep very poorly. Probably four hours a night at most.

MR: When do you go to bed?

BP: Randomly. I try to go to bed early, but then I wake up.

MR: When do you wake up in the morning for good?

BP: 5:30 to 6:00.

MR: Do you exercise?

BP: Everyday I do 21 push-ups. Which is not many. I probably could do 50. Which is not many.

MR: Do you break a sweat?

BP: I don’t sweat. And if I did, I wouldn’t admit it.

I always walk 10,000 to 15,000 steps a day just naturally by going around.

MR: Did you ever do any martial arts or sports?

BP: I was a fairly good athlete for a chess player – I’ll put it that way. I’ve played all street sports – handball, punchball, stickball.

MR: Were you a Dodgers fan?

BP: Even though I grew up in Brooklyn, I was a Yankees fan.

The first game I ever went to was a Dodgers-Giants game in 1954 at Ebbets Field. That was an interesting game because Willie Mays hit a homerun and Jackie Robinson stole second base.

MR: But you weren’t a Dodgers fan?

BP: No.

MR: How did that happen?

BP: I don’t know. I guess because originally I liked Mickey Mantle.

MR: Did you ever see this documentary The Ghosts of Flatbush Avenue?

BP: No.

MR: It’s great.

BP: Ebbets Field was the greatest field because you really felt intimate – maybe like Fenway Park or Wrigley Field – you were on top of the players.

MR: Do you still watch the Yankees?

BP: I haven’t watched a game all year. They also don’t seem to be very good this year.

Cheesse

MR: Where’s your favorite slice in the city?

BP: Well, it’s hard to compare to the old Brooklyn days.

MR: Where was your favorite?

BP: There was a place in Borough Park called Tony’s – you could get a slice for 15 cents, I think.

MR: Do you mostly eat in or order out?

BP: I do everything.

I eat a lot of cheese sandwiches.

MR: Cheese sandwiches? What kind of cheese?

BP: All kinds. Cheddar. Munster. Swiss.

MR: What kind of bread?

BP: I try to get interesting bread.

MR: From where?

BP: Trader Joe’s or some bread shop.

MR: Do you toast it?

BP: Yeah.

I also don’t mind cold bread that has come out of the freezer after I let it thaw out.

MR: Really?

BP: I like that.

MR: You like thawed bread that hasn’t been heated?

BP: Yep, as long as it’s edible.

MR: How do you put the cheese on it?

BP: If I have several cheeses, I’ll divide them up into squares and mix it up in a uniform way. If I have two slices of bread, I’ll put cheddar in a certain place and Swiss next to it in a certain way. You know, OCD-ish. I just do that naturally. I don’t have to practice it.

MR: Do you put butter on it or is it just bread and cheese?

BP: I might melt it sometimes if I want to mix them.

MR: What will you drink with it?

BP: In the morning, coffee. At later times, I might have a glass of wine.

MR: Do you prefer red or white?

BP: Red. I’m not a white wine fan. I will drink it though.

Leave it to Columbo

MR: Do you binge watch television shows?

BP: I don't binge watch, but I will watch a lot of things that people wouldn't watch anymore.

MR: What do you watch?

BP: Sometimes I'll catch a few minutes of Leave it to Beaver. I know that’s insane. I don’t know why. Perry Mason sometimes in the evening. Columbo.

What about movies?

BP: I’m a big old movie fan because my mother used to take me every week to the movies.

MR: Do you have a favorite director?

BP: I like Hitchcock and I love Vertigo.

MR: I thought you were going to say you watched a lot of Twilight Zone.

BP: I do watch a lot of Twilight Zone. I probably have seen every single one. On New Year's Eve I used to really binge watch.

MR: If you gave me a list of things, I bet I could guess with 95% certainty what you liked or didn’t like.

BP: I wouldn’t be surprised.

MR: Do you ever watch Have Gun – Will Travel?

BP: Oh yeah, he has a knight on his card.